-40%

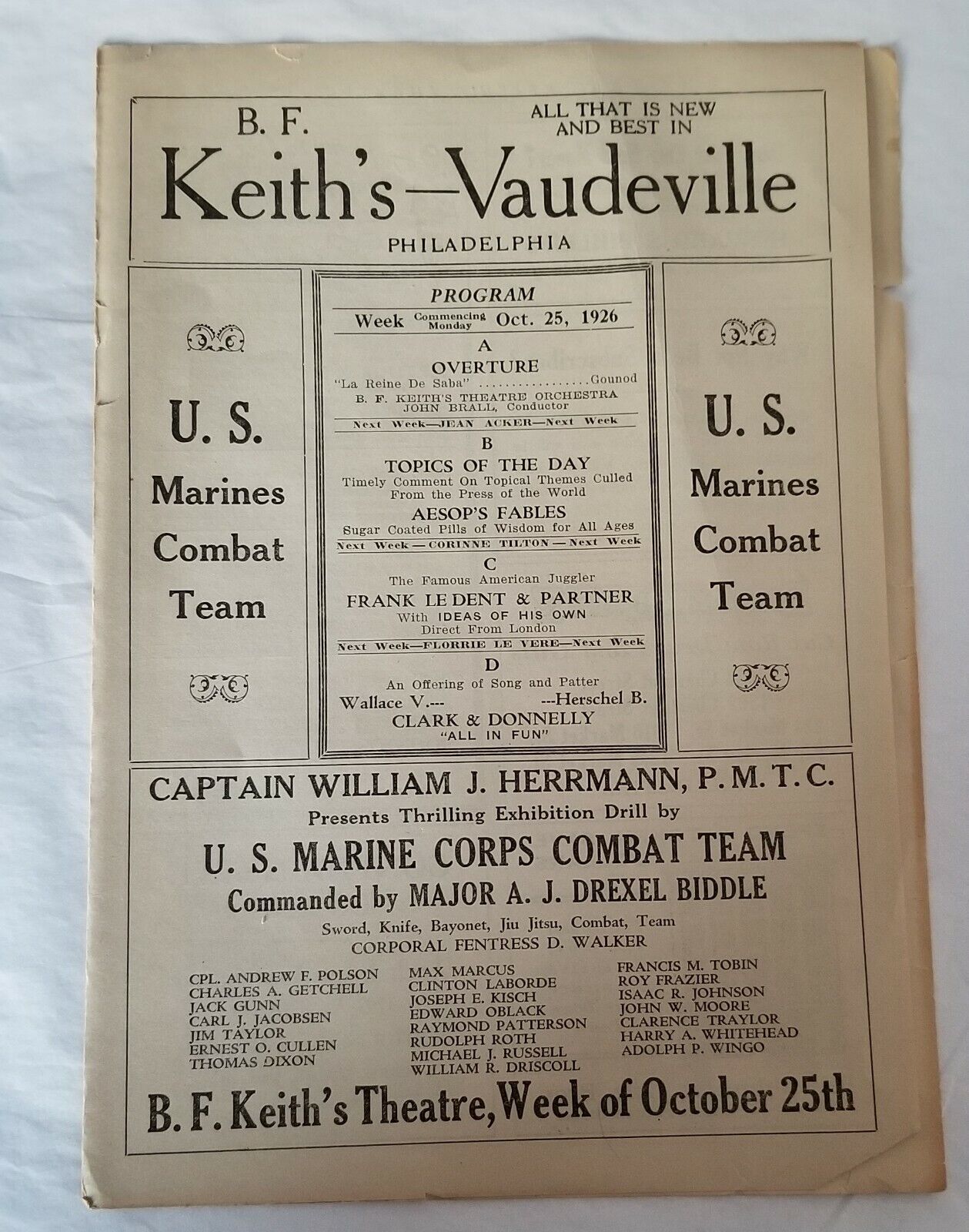

KEITH'S VAUDEVILLE, PHILADELPHIA PROGRAM - USMC COMBAT TEAM Major Drexel Biddle

$ 6.59

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

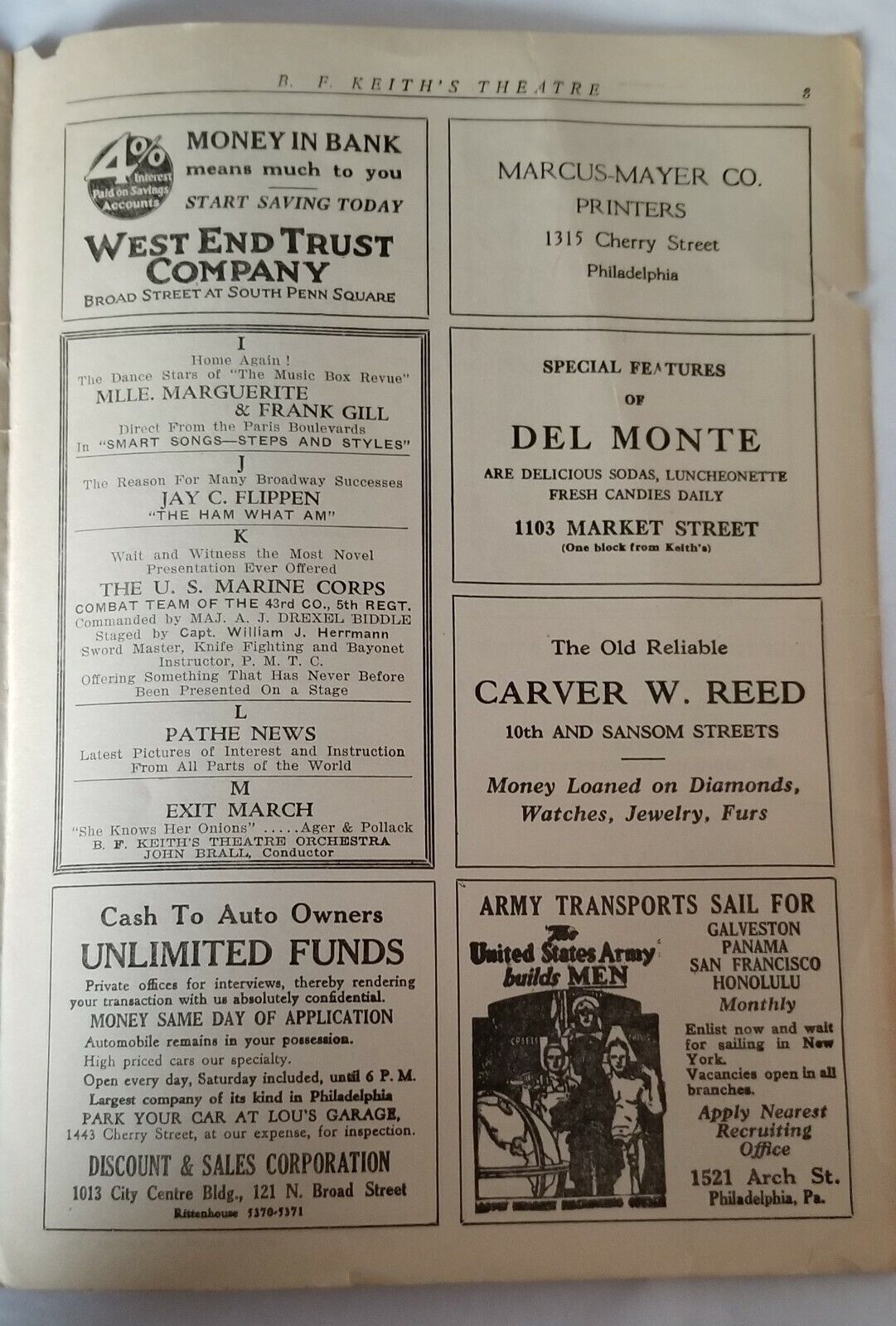

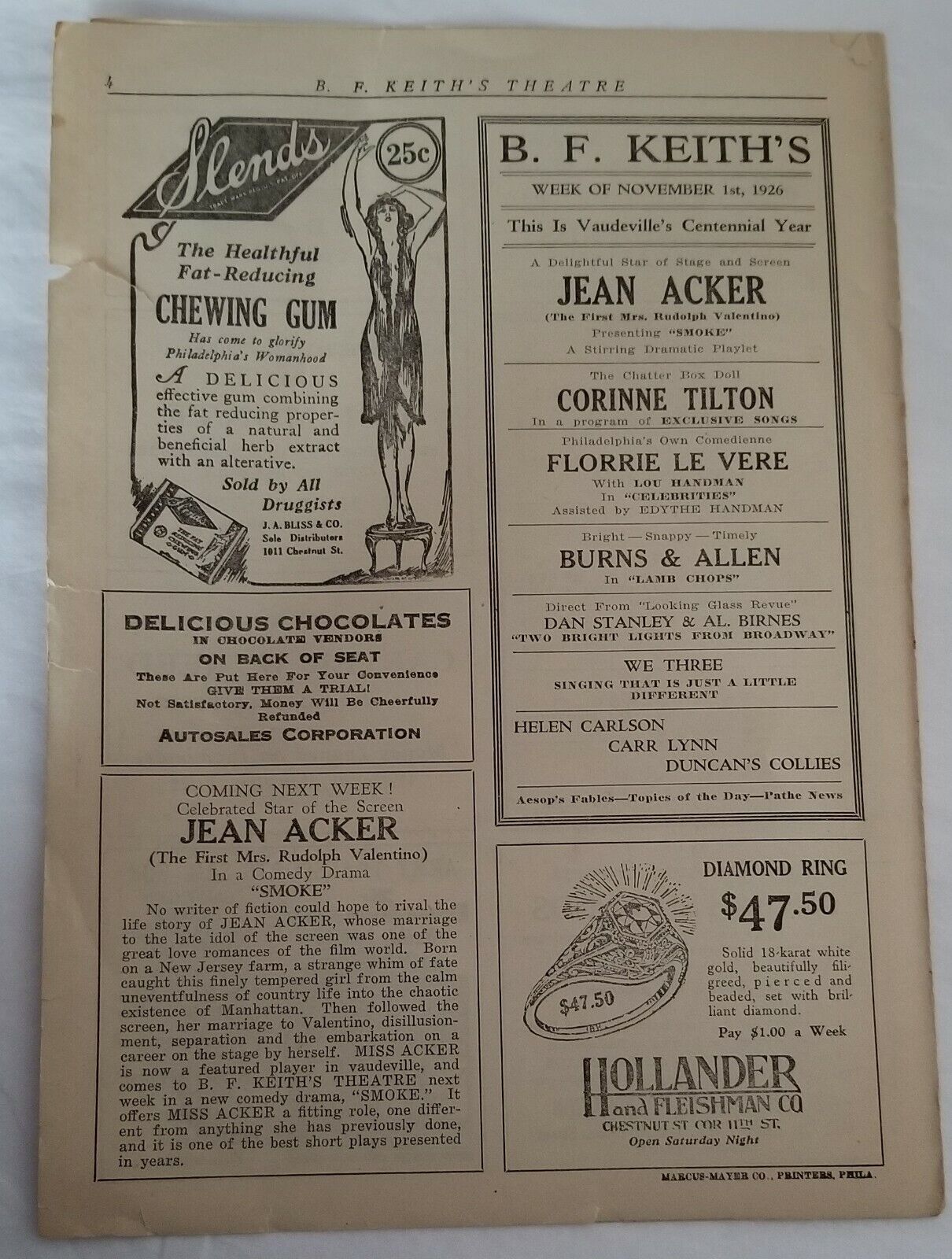

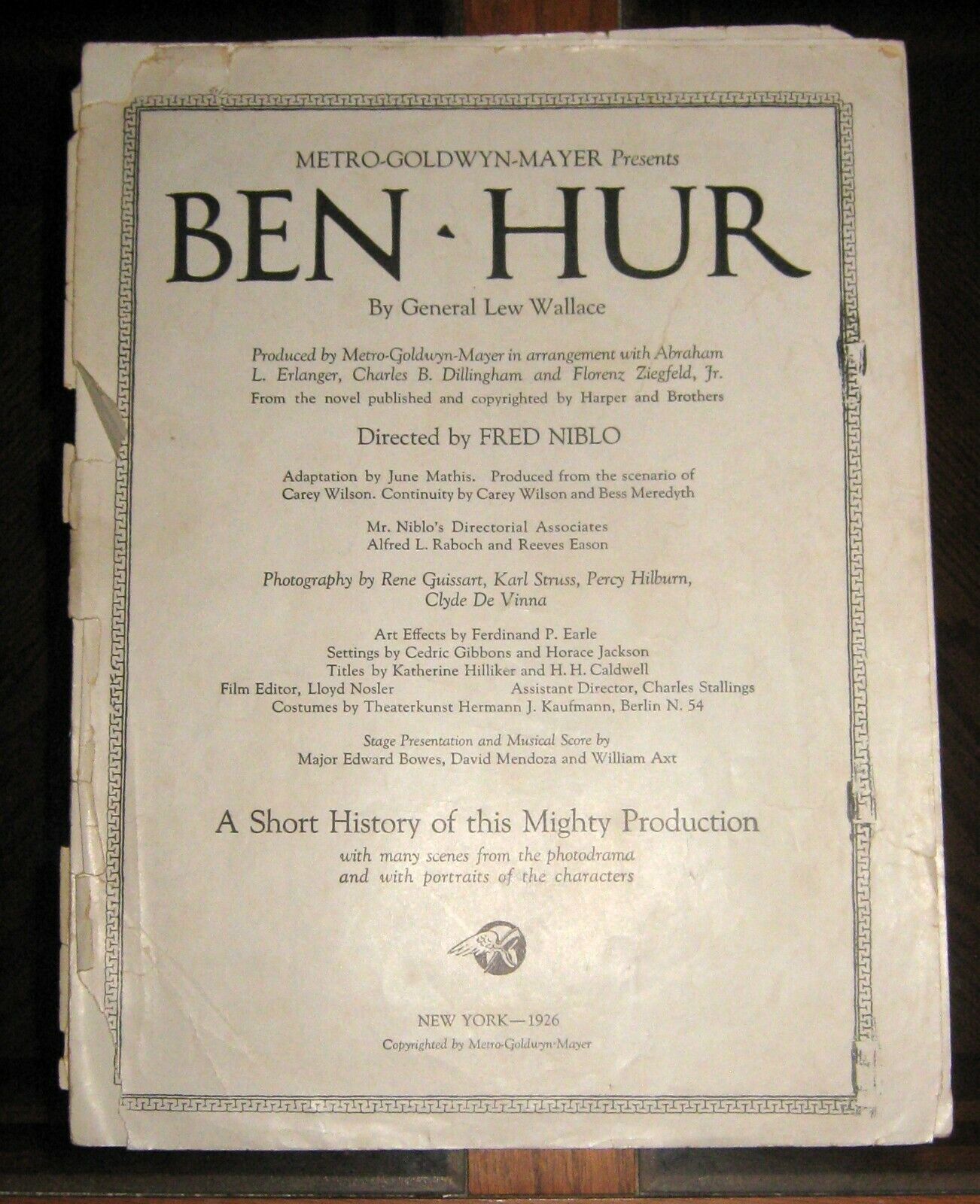

Program - " B. F. KEITH'S - VAUDEVILLE - PHILADELPHIA - Week Commencing Monday Oct. 25, 1926 " - U. S. MARINES COMBAT TEAM - CAPTAIN WILLIAM J. HERMAN, P.M.T.C. Presents Thrilling Exhibition Drill by U. S. MARINE CORPS COMBAT TEAM COMMANDED BY MAJOR A. J. DREXEL BIDDLE - SWORD, KNIFE, BAYONET, JIU JITSU, COMBAT, TEAM: Corporal Fentress D. Walker, Cpl. Andrew F. Polson, Charles Getchell, Jack Gunn, Carl Jacobsen, Jim Taylor, Ernest Cullen, Thomas Dixon, Max Marcus, Clinton Laborde, Joseph Kisch, Edward Oblack, Raymond Patterson, Rudolph Roth, Michael Russell, William Driscoll, Francis Tobin, Roy Frazier, Isaac Johnson, John Moore, Clarence Traylor, Harry Whitehead, Adolph Wingo. Includes early advertisements for drug store, U. S. Army recruiting ad, Pawn shop, Printers, Bank, Clothing, Loan Association, Jeweler, Chewing Gum, Chocolates, etc. Great old advertisiing piece. Measures 7" x 10" and in very good conditon. 4 pages. Will combine shipping when practical.Benjamin Franklin Keith (January 26, 1846 – March 26, 1914) was an American vaudeville theater owner, highly influential in the evolution of variety theater into vaudeville.[1][2]

Early years

Keith was born in Hillsboro Bridge, New Hampshire. He joined the circus (as a "candy butcher"[3]) after attending Van Amburg's Circus and then worked at Bunnell's Museum in New York City in the early 1860s. He later joined P.T. Barnum and then joined the Forepaugh Circus, before he opened a curio museum in Boston, in 1883, with Colonel William Austin. In 1885 he joined Edward Franklin Albee II, who was selling circus tickets and operating the Boston Bijou Theatre. Their opening show was on July 6, 1885. The theatre was one of the early adopters of the continuous variety show which ran from 10:00 in the morning until 11:00 at night, every day. Previously, shows ran at fixed intervals with several hours of downtime between shows. With the continuous show, you could enter the theatre at any time, and stay until you reached the point in the show where you arrived.[4]

Moving pictures

Albee and Keith opened the Union Square Theatre in New York City, and it was the site of the first American exhibition of the Lumière Cinématographe. They had obtained the exclusive American rights to the Lumière apparatus and their film output, and the first showing was on June 29, 1896. They then opened theatres in Philadelphia, and Boston, and then smaller theatres in the East and Midwest of the United States, buying out rival smaller chains. They signed a contract with Biograph Studios in 1896 which lasted until July 1905 when they switched to Edison Studios as their supplier of motion pictures. Keith and Albee merged their theatre circuit with Frederick Freeman Proctor in June 1906.

Death

Keith withdrew from business in 1909 and married for a second time on October 29, 1913, to Ethel Bird Chase (1887-1971). She was 26 years old and Keith was 67. Her father was P. B. Chase.[5]

Keith died at the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach, Florida in 1914.[1] After his son, Andrew Keith, died in 1918, control of the company went to Albee.

Legacy

In 1928, the B. F. Keith Circuit merged with the Orpheum Circuit to form the Keith-Albee-Orpheum (KAO) corporation in Marysville, Washington. In a few months, this organization became the major motion picture studio Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO). Also in 1928 the B.F. Keith Memorial Theatre opened in Boston.[6] Keith Academy and Keith Hall in Lowell, Massachusetts were named for his family in 1926. His son A. Paul Keith had donated family money to Cardinal William O'Connell.[7]

Timeline

1846 Birth in Hillsboro Bridge, New Hampshire on January 26

1883 Partnered with Colonel William Austin in Boston

1885 Partnered with Edward Franklin Albee II

1894 Opens Keith's Theatre in Boston

1896 Opens Union Square Theatre in New York City

1906 Partnered with Frederick Freeman Proctor

1909 Retires

1913 Marriage to Ethel Bird Chase (1887-1971)

1914 Death in Palm Beach, Florida on March 26

1918 Death of his son Andrew Keith (c1870-1918)

1928 His company merges with Orpheum Circuit, Inc. on January 28

The B. F. Keith Circuit was a chain of vaudeville theaters in the United States and Canada owned by Benjamin Franklin Keith for the acts that he booked. Known for a time as the United Booking Office, and under various other names, the circuit was managed by Edward Franklin Albee, who gained control of it in 1918, following the death of Keith's son Andrew Paul Keith.[1]

History

In 1928 the theaters owned by Benjamin Franklin Keith and Edward Franklin Albee and Martin Beck's Orpheum Circuit merged to form the Keith-Albee-Orpheum circuit. The combined theater chain now had over 700 theaters in the United States and Canada. They had a combined seating capacity 1.5 million. 15,000 vaudeville performers will be booked through the new entity.[2]

Benjamin Franklin Keith (B. F. Keith) was a vaudeville entrepreneur and known as the father of the “bigtime” entertainment. B.F. Keith was born in January 26, 1846 in Hillsborough Bridge, New Hampshire. He died in March 26, 1914, at The Breakers, Palm Beach Florida. Mr. Keith is best known for gentrifying vaudeville entertainment, from preceding honky-tonk entertainment, to the wholesome family entertainment for the middle-class. He had many elegant theaters throughout the United States and Canada. This article summarizes his most significant contributions for vaudeville entertainment by pointing out a few prominent themes that emerged from the cited sources.

Early influences on vaudeville

B. F. Keith left home at the age of seven to work on a farm in western Massachusetts. In the farm, he had a strongly religious upbringing. Wertheim points out that this gave him a strong sense of morality which “influenced his zealous crusade to eliminate indecency from the variety stage” and that “the farm life bred other traits that became vital to Keith’s achievements, especially the values of perseverance and thrift” necessary to becoming a strict practical businessman (5). At age 17 Mr. Keith left farming to begin his show business career in traveling circuses. While he did various jobs he was especially impressed by Amburgh's Circus that attempted to capture a mass audience. This experience provided Mr. Keith a good training ground to “Get the Coin” (his motto, meaning grab as much money as you can) while at the same time proclaiming moral purity and educational values in entertainment (McLean 32).

Mr. Keith was influenced by Tony Pastor, who worked to cleanse the stigma of the vulgar working class men-only “variety” acts . This was known as his “Respectability Mania.” Saloons, liquor, and prostitution played no part in his entertainment (Alan 105). Later, in 1883, Mr. Keith pushed this concept even further for the broader audience when he opened his Boston dime museum. At the museum, performers did continuous wholesome live variety acts in a 300-seat theater to promote entertainment for the family and not just the men. Redefining “variety” in the late 19th century was challenging however. Allan states that, “the function and meaning of variety acts differs as we move from one institutional context (the concert saloon) to another (the dime museum). Keith’s problem was not removing the taint of immorality from variety, but removing a working-class stigma from the dime museum” (114). In time though, Mr. Keith did work out through this challenge with his advisor and business partner, Edward Franklin Albee.

Partnership with Edwin Franklin Albee

The history of B. F. Keith is incomplete without his right-hand man, Edwin Franklin Albee who was a superb and penny-pinching manager from a similar background as that of Mr. Keith. Mr. Albee was born in 1857 in Machias port, on Machias Bay, Maine. When Albee was 19 he joined the P.T. Barnum Circus in 1876 and worked as a ticket seller. He also worked as a “fixer”, which was a type of advisor for the entertainment business who worked through problems of personnel and sales. Through their circus and dime museum connections they met and became friends. Like Mr. Keith, Albee also had a religious upbringing and a love of money. This made him instrumental as Mr. Keith’s advisor for transforming the museum into big time vaudeville entertainment (Wertheim 21).

Gentrifying vaudeville for the masses

As Mr. Keith’s right hand man, Albee said that he wanted his spectators “to behave as gentlemen or stay away from the theater.” Before shows would start Albee would make spectators aware of the theater policy: “When you come to this theater you are to treat the people in the audience and on the stage with respect or you are not to come here. The men and boys are to remove their hats. If you like a performer’s work you are to show your appreciation by hand-clapping. If you don’t like it, you can be silent or go out. there is to be no yelling, whistling, or hissing in this theater.” (Wertheim 30). Mr. Keith took Albee’s advice and communicated principles of courtesy to his audience in various ways. He gave his ushers strong supervisory power and he was known to rule over his employees with an iron fist, forcing them to comply with his ideas. For example, he had signs backstage that reminded the performers not to use vulgar language on the stage. Audience members who misbehaved were removed from the theater. Mr. Keith catered to the middle-class audience but kept to his strict standards.

Civility of big-time vaudeville wasn’t just communicated by rules explicitly stated, but also suggested in the classy ambience Mr. Keith created in his theaters. In time, his new approach to vaudeville had become so popular that he was pressed for space and he began to build theaters that resembled palaces. King explains the interior of the Austin Texas Palace Theater stating that “there was a commodious foyer with three doors leading to the orchestra and iron stairways rising to the balconies. Auditorium walls were done in buff and lavender and woodwork in white and gold, while the vaulted dome was as azure as the sky with floral wreaths tucked into its corner” (98). Such theaters were not new. They had already used for upper-class entertainment. What Keith did new was create elegant vaudeville houses for everyone (McLean 195). The vaudeville palace also functioned as a space were the public could escape their worries as they entered a dazzling atmosphere to be edified, mystified, and amazed.

Expansion and success of the Keith-Albee circuit

Mr. Keith did have tangles with managers of other vaudeville circuits. Smith states that Mr. Keith worked with the authoritarian principle that if you can’t lick them, buy them out or drive them out (13). He saw no problem between his religious principles and this behavior. After his death, Albee took over the powerful organization. The Keith-Albee circuit eventually controlled and subdued the competition of rivaling vaudeville managers by creating the United Booking Office (UBO) in the 1920s. This was a complex and monopolistic organization that worked as the middleman between agents and performers. In sum, the UBO ensured that Keith-Albee had virtually no competition (Smith 12). By 1915 after Mr. Keith had died, the Keith-Albee circuit controlled about 1500 theaters in the United States and Canada. In 1928 an additional 700 theaters from the Orpheum circuit merged into the Keith-Albee circuit. This made it the largest vaudeville circuit in the country. It could seat 1,500,000 people, had assets of ,000,000, and employed more than 15,000 entertainers.

Conclusion

Documents of the life of B. F. Keith are scant but we do see the large effect he had in developing American vaudeville entertainment. This brief essay gives a few themes on the life and contributions of B. F. Keith. In sum, he knew how to appeal to the masses, keep his shows clean, take good advice, and make big profits, often at the expense of others. This made him extremely successful. Further research on his life and contribution to vaudeville can done through the University of Iowa Special Collections Library (Keith/Albee Collection).

Anthony Joseph Drexel Biddle (1874-1948) was a pioneer of bayonet and hand-to-hand combat training in the US Marine Corps, and reading the New York Times (February 15, 1942), one learns that:

When the first World War started, Colonel Biddle opened a military training camp near Lansdowne [Pennsylvania], where he trained 4,000 young Philadelphians in military manoeuvres. His system then, as now, was based on long hours of callisthenics and gymnastics to harden young bodies for the rigors of the advanced training.

When he judged his charges ready for the more arduous training Colonel Biddle taught them the use of the machete, saber, dagger, bayonet, and hand grenade. He taught them also the techniques of jiu-jitsu and the French punch-and-kick man-killing attack known as savat [sic].

He was the first to give Gene Tunney, later to become heavyweight champion of the world, boxing lessons at Quantico [a US Marine base in Virginia].

That said, it is my opinion that Biddle was primarily an enthusiastic promoter. As I wrote in Kronos (1900-1939):

Biddle was a Philadelphia socialite who fancied himself a boxer, and in 1906 he began taking a first-rate professional boxer named "Philadelphia" Jack O’Brien on visits to Sunday School classes at Philadelphia’s Holy Trinity Church. Founder of a movement called Athletic Christianity that eventually boasted 300,000 members, Biddle loved telling the children how Christ had been an athlete who "had gone into the jungle [sic] for forty days to train for a match with the Devil."

Biddle also hosted boxing teas at his home. His guests included many of the best white pugilists in the country. (Although Biddle was not averse to sparring with black men, he was a man of his times, and would not invite one to eat at his table. So, when Biddle sparred with Jack Johnson in Merchantville, New Jersey in 1909, he did so incognito, using the pseudonym "Tim O’Biddle." According to his daughter’s account, Biddle came out fast, causing Johnson to tell him, "‘Now, you boy, there; don’t get yourself stirred up.’ But Father was always stirred up, and Johnson finally had to fetch him a smart whack on the side of the head to settle him.")

At Biddle’s teas, guests first sparred a few fast rounds with the host, then ate dinner with the family. ("May the good God ‘elp us to eat all wot’s on the tyble," is how Cordelia Drexel Biddle recalled Bob Fitzsimmons’s prayer.) Most guests behaved appropriately, and only the California heavyweight Al Kaufmann ever took Biddle’s boxing seriously. (Kaufman knocked Biddle out with his first punch.)

These boxing teas started "Philadelphia" Jack O’Brien to thinking about how to teach middle-aged businessmen to box without pain, a program he established in New York City during the 1920s. (You can’t learn boxing without pain, O’Brien later told A.J. Liebling, but he could teach it without pain.)

Biddle, meanwhile, joined the Marine Corps in 1917 as a 41-year old captain. He toured British and French training camps in 1918, and then convinced Headquarters Marine Corps to make boxing part of Marine Corps recruit training. The style taught was essentially English amateur boxing. Although said to closely resemble rifle-bayonet fighting methods, the boxing was useful mostly for increasing recruits’ physical self-confidence.

After the war, Biddle stayed in the Marine Corps Reserve. In 1919 he exhibited rifle-bayonet fencing before the Willard-Dempsey prizefight, thereby delaying the main event because after the Marines scuffed up the canvas, it was no longer usable for fighting. Biddle also supported the legalization of boxing in New York, and during a 1922 court case charging Tex Rickard with sexually assaulting teenaged prostitutes, Biddle said, "Rickard is the finest and noblest sportsman I ever knew." During the 1930s, Biddle taught close combat to FBI agents, a job he owed in part to a relative who was Franklin Roosevelt’s Attorney General.

In 1937, the Marine Corps Association published Biddle’s book, Do or Die, Military Manual of Advanced Science in Individual Combat. While the boxing tips from Bob Fitzsimmons were good and the self-defense techniques cribbed from W.E. Fairbairn were passable, the rest of the book showed considerable ignorance of the realities of a mid-twentieth century battlefield. (If nothing else, during World War II the Western Allies, Germans, and Russians preferred to conduct their trench warfare with tanks and flamethrowers rather than bayonets and entrenching tools.)

Recalled to active duty during World War II as a close combat instructor for the Marine Corps, Biddle died in 1948 at the age of 73.

Whether you view Biddle as an important pioneer or just a wealthy enthusiast, Cold Steel, by his student John Styers, remains a classic of the genre. Furthermore, his personal history is both colorful and well documented. As a result, I believe it would reward a detailed study. The following are some suggestions about where that project might begin.

General

Biddle’s obituary appeared in the New York Times on May 28, 1948. See also Who Was Who in America, 2, (1943-1950), 1971, 61-62.

Columnist Westbrook Pegler apparently wrote about Biddle in 1947. Unfortunately I have not seen the material, so do not know what it says. See http://www.hoover.nara.gov/research/historicalmaterials/other/pegler.htm.

Biddle’s Boxing

An enthusiastic amateur boxer, Biddle boxed a 2-round public exhibition with Bob Fitzsimmons in 1893 and a 4-round public exhibition with "Philadelphia" Jack O’Brien in 1908. See http://www.fitzsimmons.co.nz/html/facts.html and http://www.cyberboxingzone.com/boxing/obrien.htm. As noted above, O’Brien specialized in training celebrities, and his comment to Liebling, which originally appeared in New Yorker, was reprinted in Liebling’s A Neutral Corner, edited by Fred Warner and James Barbour (New York: Fireside Books, 1990). However, in fairness, it must be noted that Biddle did have a punch, and during a public altercation with a streetcar conductor in Atlantic City, it was Biddle in one. See John McPhee’s essay "In the Search for Marvin Gardens," which appeared in his book Pieces of the Frame (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1975).

In A Flame of Pure Fire: Jack Dempsey and the Roaring ‘20s (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1999), Roger Kahn discussed Biddle’s influence on the legalization of boxing in New York following World War I. Personally, I believe that this was Biddle’s most enduring contribution to American combatives.

During the 1920s, Biddle’s favorite heavyweight boxer was Gene Tunney, and during the 1920s Biddle was often seen in the corner of "The Fighting Marine." See, for example, http://bally.fortunecity.com/mayo/239/tunney.book.long.count.chapter.4.txt.html.

Biddle’s Influence on WWI Combatives

In June 1917, Biddle was a captain assigned to the Marine Barracks at Port Royal, South Carolina. (The post wasn’t renamed Paris Island until later that month, nor the spelling changed to two R’s until May 1919.) For a brief mention of Captain Biddle and Marine recruit training, see Joe Rendinell’s diary at http://perso.club-internet.fr/batmarn2/joerendi.htm. For a post history, see Elmore A. Champie, A Brief History of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina, 1891-1962 (Washington, DC: US Marine Corps, 1962), reprinted at http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/usmchist/parris.txt.

In 1918, Biddle trained a USMC bayonet demonstration at Lansdowne, Pennsylvania. Lansdowne is a Philadelphia suburb located about ten miles west of downtown on the Main Line, and Drexel Hill, where the Biddle family lived, is nearby. There is a brief mention of the Lansdowne site in The United States in the World War by Major Edwin N. McClellan (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 1920). This book appears online at http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/usmchist/war.txt.

For a description of US bayonet training program of the era, see William J. Jacomb, Boxing for Beginners with Chapter Showing Its Relationship to Bayonet Fighting (Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1918). For a photograph showing the boxing instruction that accompanied US military bayonet training, see http://raven.cc.ukans.edu/~kansite/ww_one/photos/bin15/imag1469.jpg. This is actually the center panel of a panorama; for the complete photo, see http://www-cgsc.army.mil/dsa/CGSOC9900/briefings/panoramicphoto/briefing/sld007.htm. The title is "337th Infantry, ‘World’s Largest Boxing Class,’ conducted by Billy Armstrong, 27 Jun 1918," and the location is Camp Custer, Michigan.

Biddle’s Influence on WWII Combatives

A discussion of Biddle’s influence on WWII combatives appears at Blade Forums, http://www.bladeforums.com/ubb/Forum35/HTML/000301.html. It is a very long thread, so some borrowings follow:

"Biddle’s Do or Die is really quite vague, so it would be hard to say what he actually taught and what he didn’t."

"From the biography of Biddle in the book, his techniques, and what I have read about him from other authors, it would appear that he was a very skilled fencer with sabre type weapons. His techniques are very viable in the dueling range as long as you have a ‘big’ knife, but anything shorter than 9" or so on the blade length probably won’t be compatible with all of his techniques."

Attributed to Rex Applegate. "I met both Biddle and Styers at Quantico and witnessed demonstrations with bayonets. Biddle was a dilettante and a showman. Both used a duelist approach that was bull**** and not based on practical experience like that of the British." (To which another contributor added that Applegate was teaching an unrelated system of his own, and so had a bias.)

"When I was learning about knife fighting there were 3 basic ‘schools’-- the Fencing method (Styers, Biddle); the Shanghai method (Fairbairn, Applegate); and the Modernist method. See Modern American Fighting Knives by Robert S. McKay for more info about this."

"Biddle’s knifework is often deemed impractical when people try it with folders or modern ‘fighting’ knives. I suspect it worked much better with that long bayonet he uses in Do or Die."

From William L. Cassidy, The Complete Book of Knife Fighting (Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 1993), ISBN 0 87364 029 2:

So strong was Biddle’s indoctrination into the use of the sword, that his entire method of [knife combat] instruction is built around such maneuvers as In-quartata, Passata Sotto, and other, similar movements well known to the duellist. In spite of his introductory remarks, nowhere does Biddle acknowledge that the users of ‘dagger, machete or bolo’ may not have been gentlemen, well-schooled in the tenets of swordsmanship and fair play. This was Biddle’s greatest weakness. He was a gentleman instructing gentlemen in the ritual of knife fighting. As such, many of the methods he advocated come down to us as nothing more than quaint reminders of an earlier (and perhaps better) age of conflict…